In contemporary American society, we hear a lot of organizations compared to “family.” You’ve probably heard someone say in a meeting, “we’re family here!” Even Olive Garden’s long-standing slogan has been, “When You’re Here, You’re Family” (though, for some reason, they still want me to pay for the food even though I’m family!).

You’ve also likely heard a pastor refer to the local church as a family. If you are or have been a pastor, you’ve almost certainly used familial language to describe your church’s culture at one point or another.

Family language pervades organizational language today. That’s not inherently a bad thing. As human beings, we long for a sense of belonging. We instinctively seek out and cling to a variety of kin-like relationships that fill our most subconscious needs for belonging and safety.

Understanding Family

And contrary to what we think of here in the West when we think of “family” (i.e., the “nuclear family” unit consisting of parents and children), throughout the world and throughout history, the concept of family has often been more broadly applied. In many parts of the world, when people speak of family they speak of what we in the West call our “extended family.” In other parts still, that circle is broadened to include the family ancestors.

Anthropologists also describe another phenomenon known as “fictive kinship” or “chosen kinship.” It is the embrace of non-blood relationships as though they were family. It is the constitution of familial bonds that do not share common genes. We find examples of this sort of family in multiple places in our society. When we speak of a friend as “like a sister” or “like a brother,” we’re speaking of fictive kinship. For better or for worse, gangs are built in no small part on the basis of providing fictive kinship to its membership where biological kinship has failed.

The ideal picture of the Church is one of fictive kinship. What began as early Christians embracing, providing for, and entering into the rhythms of life together like chosen sisters and brothers, mothers and fathers, has continued (to various degrees of health or dysfunction) through the centuries. While most local churches in the United States don’t function as fictive kin in the way our spiritual ancestors did, if you’re like me and grew up in church, you may remember referring to people as “brother” so-and-so and “sister” so-and-so. Even as late as 2005, when I attended Central Bible College, the expectation was that if a professor was not a doctor, they would be referred to as “brother” or “sister.” This finds its roots in the ancient view that when Christians come together we are a chosen family, with God as our Father and the (capital C) Church as our mother (I unpack the latter a bit in this post).

But not all families are created equally. Not all families function healthily. So the question remains, if the Church is to be a family, what type of family is it?

Church as Cosa Nostra

When churches refer to themselves as “family” one of the dangers is in how “family” is lived out in the life of the church. There is a danger for churches to function like family in a pattern we see played out most acutely in the history of the Cosa Nostra—that is, the mafia.

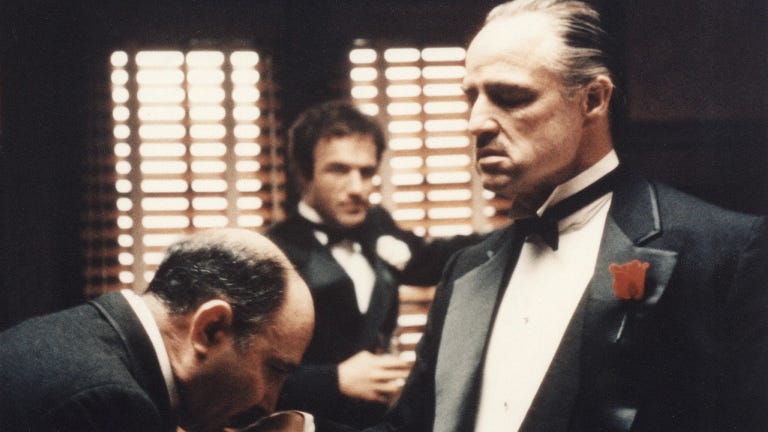

If you’ve watched classic mobster movies like The Godfather, Goodfellas, or Donnie Brasco, you will see a version of chosen family on display. But the power dynamics of this sort of family (and other gang-like structures) is very different. At the heart of this “family” is a code of unquestioned loyalty that ascends up the hierarchal ladder to the family boss. This “familial” disposition is often one-sided—family for me, business for thee.

Churches can function the same way if they’re not careful. We can be “family” when we talk about sacrifice of volunteers to give their time and talent, of the generosity of members to give their tithe, and of staff to be patient or forgiving when unforeseen changes disproportionately disadvantage them. But we have the tendency in modern church to switch to “business” mode when the sacrifice is to seek the welfare of someone who has been mistreated in our community at the expense of our public image, when the generosity is extended to the systemically poor in our communities, or when a staff member or church member voices concern or disagreement.

When we demand family fealty and sacrifice without the reciprocal generosity and mutuality that comes with healthy family, we come dangerously close to church functioning more like the Cosa Nostra than the vision of the New Testament church. Asking people to sign both membership covenants and non-disparagement agreements reveal an incompatible tension between a biblical vision for church as chosen kin and a modern American vision for church as corporation. When we choose public image over the righteousness that demands we protect the vulnerable in our midst, we betray a reality that devotion and loyalty only flows toward centers of power. And this is not the vision God has for his church. We should model our notion of family after the New Testament church rather than a New York crime syndicate.

Church as Covenantal Family

Much of the reason I believe we often have a thwarted familial life within our churches (though this extends to the business and non-profit worlds as well) is that many of us have a fractured understanding of what covenantal family is. So I want to offer a few suggestions on how to reframe toward a more biblically faithful view of church as family:

First, being in covenantal family with the church is about the community not the incorporated entity. In the United States, part of a church’s existence is that it has an incorporated and organized component to it. Churches are a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization, incorporated with their local state government. As such, they are required to have articles of incorporation, a governing board, and more. And because part of modern church has become about marketing that organizational entity, there is an element to church that is a brand as well. But our belonging (and with it, our loyalty) is not to the incorporated entity, nor is it to the brand. It is with the people of God, the timeless and universal church that finds its incarnated expression among our local church community, not the brand. This means, when the interests of the church people and the church corporation are at odds, it is the people to whom we give priority. They’re our family, not the organization that gives structure to the community.

Second, covenants are not the same thing as contracts. The nature of covenant is so immense and deep that it warrants a collection of posts on its own. If you have opportunity to sit with Messianic Jewish believers and listen to them discuss what it means to be in covenant, I promise you won’t be disappointed. But covenant is a mutual agreement between parties in which promises of self-giving and self-sacrifice are made between both. The preservation of the relationship the covenant is intended to protect is the chief aim and a covenant is not considered nullified until it is clear that the relationship is fractured beyond repair.

This means that when we in local churches speak of membership and belonging in covenantal terms, we are not simply using churchy words to describe membership…we’re describing something altogether different—and it is something that we are binding ourselves to inasmuch as we ask a congregant to bind themselves to. We are committing to protect the people, to provide for the people, to be loyal to the people. We are pledging something incredibly holy, enduring, and long-lasting. When we speak of entering a membership covenant, we’re effectively committing to the welfare of that family if needed, potentially even if they leave the church. That’s a serious, serious undertaking that shouldn’t be spoken of as lightly and cavalier as it is. And it definitely shouldn’t be the one-sided sort of loyalty/tithing pledge it is often made out to be.

Third, policies and rules need to serve relationships, not the other way around. Central to covenantally bonded family is the notion that policies and rules function like a trellis to a grapevine—they exist to give the grapevine support but are not intended to stifle or limit the plant’s growth. The trellis “serves” the grapevine, the grapevine doesn’t serve the trellis.

Unlike our rules-obsessed culture that views relationships being defined and confined by rules, the covenantal cultures of the ancient world were very different. Rules gave structure to relationships insofar as the rules promoted relational harmony, but exceptions to rules were often given if the rules no longer served the flourishing of the relationship. So while we might point to a benevolence policy in our church as a reason we can’t help a member who has been out of work for an extended period of time, covenantal living says, “the heck with the rule, we take care of our people.” Discernment and wisdom are central to exercising those exceptions—but the idea of pointing to policy to justify not helping people is not only not familial, it’s not biblical.

Finally, covenantal families promote egalitarian distribution of power. The notion that a church vision must be given to a Moses-like pastoral figure atop Mt. Sinai and received unquestioned by the masses the Mosaic figure leads is a Cosa Nostra form of familial living, not one of covenantal family. In church as covenantal family, vision arises from the community discerning together, revising and reforming as God adds to their number. It is a living, breathing, agile vision that responds not just to what the Holy Spirit did when he birthed the dream of that church, but what he’s doing in the moment and what he desires to do in the future. The vision belongs to the people because the people have had a part in cultivating the vision.

What’s more, the power that undergirds the community is evenly distributed. There are no people who are “next level leaders” (i.e. can’t be questioned or held accountable). There are no haves and have nots. There’s no oppressive hierarchies, but only structures of authority and responsibility that promote flourishing. Covenantal families seek the welfare and the input of those who have the potential to be most vulnerable among them—women, ethnic minorities, immigrants, the poor, etc. It is a vision of the kingdom where the only king is King Jesus.

Concluding Thoughts

My hope is that the next time you hear someone, whether it’s a church leader or a boss—or the waiter at Olive Garden—say “we’re family here!” you will ask, “what kind of family?” My hope is that we pastors would begin to move away from simply using familial language because that’s what the cool kids do these days and instead genuinely inspect what kind of family we want to be, and to be honest about it. It’s my earnest desire that we would move away from traits that resemble the Cosa Nostra and move toward a more biblical faithful form of covenantal living together, where people can flourish not based on their demonstrated expressions of loyalty to a brand, but because in Christian family, we’re knit together and responsible to care for one another.

My gut instinct that the latter—a pattern of covenantal family—is precisely what is needed in a culture where a healthy vision of family has been eroded by consumerist and bureaucratic endgames. People long for family that actually functions like family. And there’s no social institution better poised to provide that to society than the local church. It’s up to us whether or not we want to be that.