Over the last several years, renewed attention has been given to the idea of people having a “biblical worldview.” In church and church-adjacent ministry we create content aimed at giving people a biblical worldview, some will push a specific product or their brand as promoting a biblical worldview, and even research organizations have attempted to define how much of the American population possesses a biblical worldview.

The problem is that the phrase “biblical worldview” is something of a Rorschach test—you know, those inkblot tests we’ve all done in which we interpret the image we see…but in doing so, unwittingly project our psychological interpretations onto the image. So we might say we see the image of a butterfly, but in reality we’re telling the test giver that our mother was emotionally aloof during our childhood.

The term “biblical worldview” is a theological inkblot test. Meaning, when we use the word, we often project our own meaning onto it, instead of establishing an actual, defined concept of what it means to possess a biblical worldview. In this, we create two unintentional errors:

When we say we want people to have a biblical worldview, we tend to mean we want people to believe the right things about the Bible and,

As I noted in a recent tweet, when we say we want people to have a biblical worldview, we mean that we want them to believe the right things about the Bible as we believe.

Therefore, when a white American evangelical uses the term he or she most often is referring to adopting a reading of Scripture that aligns with what white American evangelicals typically believe to be true. While reading the Bible like a white American evangelical isn’t inherently, nor universally wrong, it isn’t a “biblical worldview.”

So the question remains, is there such a thing as a biblical worldview? And if there is, what the heck is it?

There’s certainly debate on whether there is such a thing, but I tend to believe there is. But let’s hit on some key points before we get into that:

A “worldview” is not an ideology. I’ll unpack that more in a moment, but in popular level discourse we often conflate worldview with an ideology, specifically in political speech on topics like Critical Race Theory (CRT). By CRT is not, by any stretch of the imagination a “worldview” by itself. It’s simply an academic theory, upheld by any number of similar ideologies. Capitalism, marxism, etc…not worldview. Those are socio-economic systems. We have a tendency to just package everything we don’t like or desire to critique or boogeyman and call it a worldview—because it sounds scarier that way. But it’s simply not true.

A culture’s worldview is fluid and ever-changing. Human worldviews, expressed in human cultures are constantly changing. While seismic changes in the world (what I call “inflection events” below)…things like 9/11 and COVID-19 can affect quick and significant change on how a culture’s worldview changes, most worldviews slowly change overtime, like the erosion of rocks buffeted by ocean waves. But when we compare over time—say what was considered masculine attire in 17th century France versus today, we can see that change in action. Where, in America a few generations ago, it was considered normative for fathers to be emotionally aloof disciplinarians and providers, today’s millennial father places high value on emotional intelligence and presence with his kids. This is an example of a long-form fruit of worldview change.

Not even the cultures of the Bible embody a biblical worldview. This is a tough pill to swallow, but none of the cultures in the Bible perfectly embody a “biblical worldview.” Even the culture(s) depicted in ancient Israel and Judah, represent significantly different worldviews in each epoch of time…in Egyptian captivity, the united monarchy period, the divided monarchy, the exile, second temple, etc…are all periods of biblical history in which the Jewish people embodied different worldviews. And in many instances throughout Scripture—such as the polytheistic leanings of post-captivity Hebrews at the foot of Mt Sinai, confrontation of David by Nathan, the prejudice of Jonah toward the people of Nineveh, etc.—Scripture describes God actually confronting and rebuking the Bible.

Yours and my culture does not embody a biblical worldview. You may be inclined to strongly agree and see this as justification for whatever pet culture war du jour we’re engaged in, but we participate within our cultures, we don’t stand outside of them, unaffected by them. My own worldview, your own worldview, does not perfectly embody a biblical worldview. It is a sign of spiritual and emotional maturity to recognize that there’s a lot about how you and I see the world that may be right, and a whole lot that those who think differently than us may understand better.

What is a Worldview?

Before we can understand what a biblical worldview is, let’s take a look at what a worldview of any sort is. For this I lean heavily upon and heartily recommend the work of the late Christian anthropologist Paul Hiebert, especially in his work Transforming Worldviews. While I tweak some of his work to bring clarity or, in some instances, additions I believe are necessary, much of what follows is a synopsis of his work.

Hiebert defines a worldview as,

The foundational cognitive, affective, and evaluative assumptions and frameworks a group of people makes about the nature of reality which they use to order their lives. (Emphasis added)

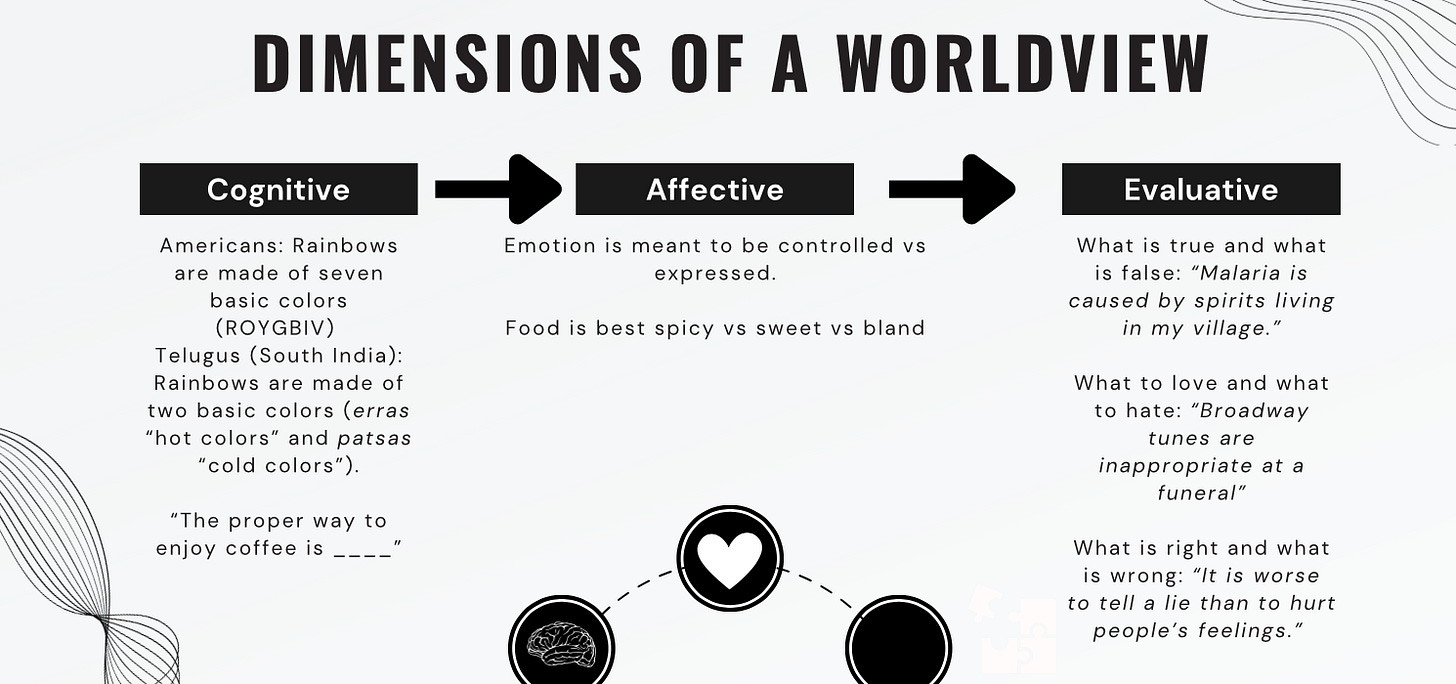

Let’s unpack that a bit. Hiebert says that a worldview has three dimensions, each deeper than the last:

A cognitive dimension: our knowledge, logic, wisdom, etc.

An affective dimension: our feelings, aesthetic preferences, notions of beauty, loves.

An evaluative dimension: our ethics, values, unspoken norms.

I recently gave a lecture to the Doctor of Missiology students at Southeastern University in which I illustrated each of these dimensions like this:

In the West, we tend to place much greater focus on the cognitive dimension of a worldview—especially as it pertains to how we disciple people along in the faith. If we can get people the right “content,” we will disciple them into the faith. But Hiebert notes that we paying attention to the cognitive dimension alone produces what a sort of “evolved paganism”…meaning that people may adopt some Christian ideas, but ultimately retain the practices and patterns they possessed before being introduced to Christ.

Hiebert also says that paying attention to the cognitive and affective dimensions alone produces syncretism…a blend of Christianity with folk religion, or as some call it “cultural Christianity. This is the ill-discipled brand of Christianity we saw attempt to sack the U.S. Capitol building on January 6, 2021. It is a sort of Christianity that believes the “right” things, and may not smoke, cuss, or cheat on their spouse…but at its core, it possesses a worldview that is inherently more “American” than it is “Christian.” It is this lack of transformation of the evaluative dimension, a neglect of forming virtues and ethics, that lies at the heart of the American discipleship crisis.

How Our Worldview Works.

As illustrated in the figure above, our worldviews are constantly, though very subtly, changing based upon the experiences we have and how the interpretation of those experiences produce decisions and consequences. Our every day experiences, as well as large inflection events like the Great Recession, are inputted into our minds and interpreted through the three dimensions of our worldview. How we interpret those experiences result in the decisions we make and our decisions (obviously) result in consequences (i.e., products of decisions), whether good, bad, or neutral. But the products of decisions create new experiences, which repeat the cycle over again.

So, for example, if I have an experience where I lose all of my possessions, and I interpret those events in desperation, I might decide to rob a bank. If I rob a bank, I’ll almost certainly be arrested and prosecuted…which creates a whole new set of experiences, that will consequently shape my worldview. This is an extreme example, but helps to illustrate how things work.

Defining and Constructing a Biblical Worldview

If we take into consideration that human beings live within an inherently broken world, in rebellion against God, then we must accept the fact that we ourselves, the cultures in which we live, and the worldviews we carry are also inherently broken. That doesn’t mean they’re completely bad, but rather imperfect. Thus, establishing what a biblical worldview is, requires looking to the One who embodies perfectly the ideal of what it means to be human: Jesus.

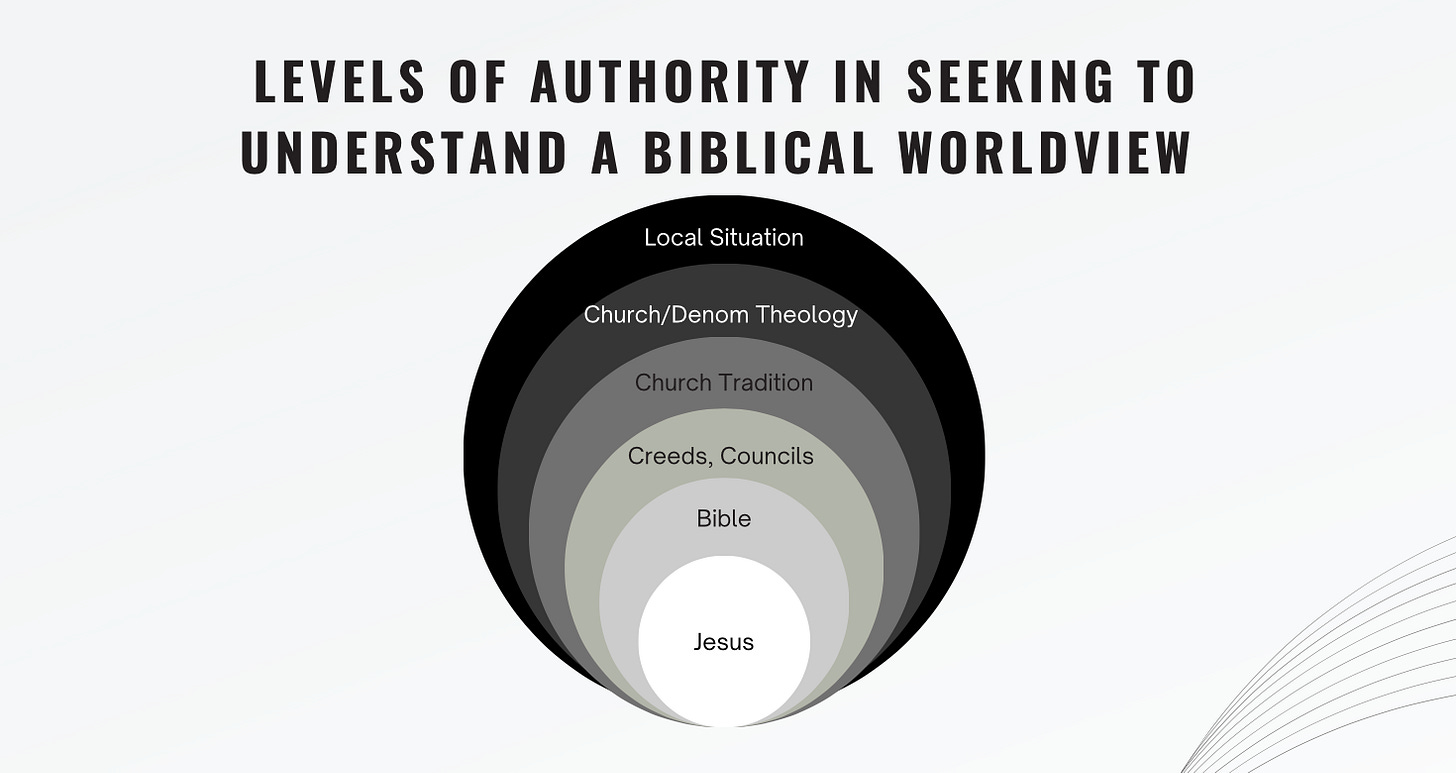

A biblical worldview is the worldview of Jesus. Therefore, as we transform into the likeness of Christ—in every dimension of our existence—we grow into a biblical worldview. Doing this requires that we consider varying levels of outside authority that help form us toward that Jesus-focused end, as illustrated below:

As we can see illustrated, as we consider Jesus as the lens through which we read everything, even the Bible, we also consider the input of the Great Tradition of faith and our more localized communities of faith in informing our worldview. Jesus remains the anchor throughout all of that, but without that external input we are prone to interpreting Jesus through our own individualized lens, and are prone to error.

But formation toward a biblical worldview, the worldview of Christ, requires intentional attention given to helping people form godly ethics, values, and norms…to see their very existence through the power of the gospel…to be, as it were, radicalized by the Sermon on the Mount (which is, effectively, a blueprint of kingdom ethics).

Components of a Biblical Worldview

Hiebert attempts to articulate what he views as components to a biblical worldview, using his cognitive, affective, evaluative framework. I’ve adapted portions of his framework in the following graphic:

As you can see, this looks quite different than answering whether or not someone believes in the inerrancy of Scripture or attends church regularly. This are broader themes that each require lifelong pursuit. In that regard, until the final resurrection, a biblical worldview is more of a journey to pursue than it is a destination to reach.

A couple notes that require elaboration:

On the difference between “organic/mechanistic” I’m referring to both the life and growth of the church and, more granular still, how relationships are cultivated and maintained.

The mysterium tremendum is a latin term that roughly means “holy awe.” I the Isaiah 6, “I am undone!” sort of feeling when we recognize God’s holy presence as something very much uncommon and “other than.”

But how do we change our worldview? How do we help people change their own?

Changing a Worldview

Hiebert also suggests that there are three ways we can intentionally direct the changing of a worldview:

Examining our worldviews. That is, to “surface them.” Our worldview is largely mysterious, implicit, unnamed. But by bringing to the surface what we do, it helps us examine it more objectively. Why do Westerners interact the way we do? Why do we view time and relationships and family and good versus bad the way we do?

Exposure to other worldviews. Once we realize how we perceive concepts like time and family, it can be jarring at first to discover that people in other cultures—people who love Jesus and their communities and their families just like we do—don’t view those things the same way. When I, as an American, think of “family”, my mind generally goes to my wife and my children…what we would call our “nuclear family.” But in many parts of the world “family” includes grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins, etc., and in still other parts of the world includes deceased ancestors. By learning that many throughout the world think about very basic things differently than we do—including the cultures of the Bible, it helps us realize that what we consider “normal” isn’t normal to all.

Create living rituals. For those of us in church traditions and cultures that don’t have many rituals, this may seem odd or even against our natural impulsive. But rituals, as Hiebert says, “speak to the transcendent—of our deepest beliefs, feelings, and values…they point to mystery…fundamental allegiances, and express our deepest emotions and moral order.” But rituals for rituals sake are not the point. We must connect ritual, especially in the church, to deep meaning and allow it to structure and express our worldview.

Conclusion

It takes far more intentionality to walk with people toward a biblical worldview when considering what we’ve discussed. It requires that we look at formation not simply as the right content, the right transformational events (conferences, services, etc.), or policing the right behaviors. Instead, it is a deeper call toward being formed into the image of Christ. But this deeper formation results in deeper, longer lasting change as we partner with the Holy Spirit to bring transformation, not simply the surface of an individual or of a society, but to the very core.

For more information, see:

Georges, Jayson. 2017. The 3D Gospel: Ministry in Guilt, Shame, and Fear Cultures. Time Press.

Hiebert, Paul. 2008. Transforming Worldviews: An Anthropological Understanding of How People Change. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker.

McCaulley, Esau. 2020. Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope. Downers Grove, IL: IVP.

Richards, E. Randolph and Brandon J. O’Brien. 2012. Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes: Removing Cultural Blinders to Better Understand the Bible. Downer’s Grove, IL: IVP.