What we actually mean when we say "Spiritual" and "Physical"

Church Words Revisited Series: Part 1

Introduction to Church Words Revisited

Do you remember when you were young and you’d repeat a word so frequently in short succession that it’d eventually lose its meaning? If you’re not sure what I'm talking about, right now say to yourself the word “banana.”

Now, repeat the word over and over again. After a number of repeats, the yellow fruit you inevitably thought of when you first said the word begins to fade and the word itself begins to become a jumbled mess, losing its meaning because of excess use.

This is because words are auditory symbols. They’re a verbal cue spoken from one person, meant to illicit an image in the mind of another in order to form a basis of understanding in human communication. Like any other symbol, its overuse can erode its connection to the meaning it’s designed to point us toward.

Take the word “friend,” for example. There are some cultures that draw very finite lines between what differentiates a “friend” from simply someone you know—and acquaintance. In American culture, the word is so wildly applied—whether it be to refer to one’s Facebook connections, or even how my daughters’ teachers refer to other classmates when speaking to a student—that the meaning of the term “friend” is almost unrecognizable from what it was a century ago.

We have words like this in the church world, too. Words like “gospel” and “kingdom” and “mission”—words that we use so frequently and to which we are so dependent, that we have often lost their meaning. But these words are essential. They help us make sense of the world around us, and of how we are called by God to interact with that world.

That’s why over the next several weeks, or months, I’ll occasionally drop in a new edition of “Church Words Revisited.” I probably won’t do them all in succession, as I prefer to leave it open-ended. But my hope is that it will help brings some clarity where confusion otherwise exists.

Spiritual vs. Physical

Often, when we speak of the “spiritual” and the “physical,” we speak of them as opposite from one another. The spiritual is that which is immaterial, supernatural, or unseen. The physical, by contrast, is that which is material, natural, and seen. As such, Christians tend to divide the world this way:

Thus, we categorize that which is unseen as “supernatural,” that which transcends—even supersedes—the natural order. We tend to think of the spiritual/supernatural as superior and the physical/natural as inferior. And when God wants to do something in his creation, he must suspend the natural order in order to intervene.

But what if I told you that this thinking doesn’t come from Scripture? That, in fact, this sort of way of seeing creation would have been almost entirely foreign to the ancient Jews who wrote and first received the Scriptures? We see the words “spiritual” and “physical” in Scripture, especially in relation to the way Paul talks about the resurrected body (more on that in a bit), but when we read Scriptures words, taking them to mean they are referring to a framework like above, we’re actually reading our Enlightenment-informed perspectives back into the text. We’re not allowing our cosmology to be formed by the text.

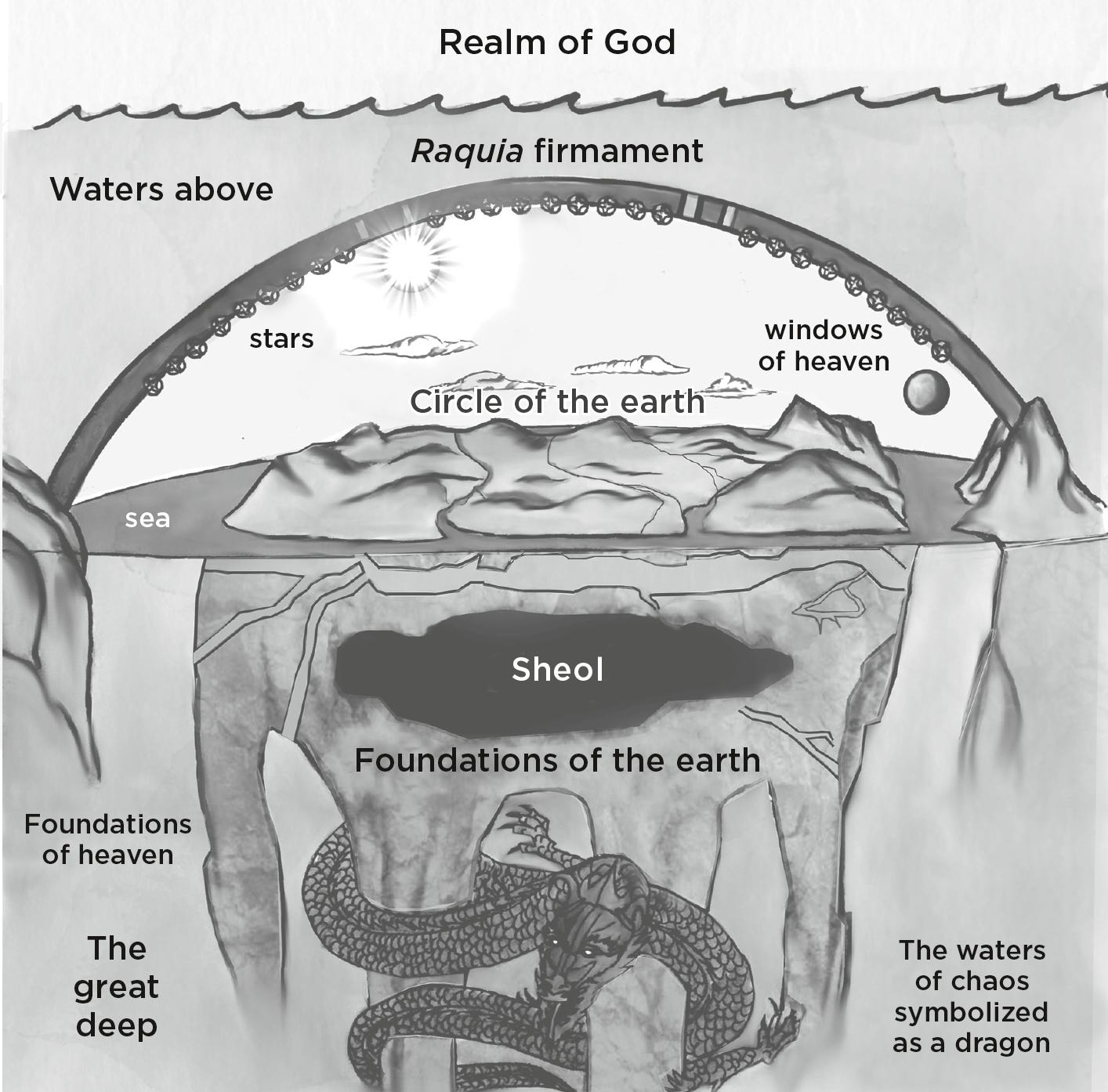

Instead of the cosmic framework illustrated above, ancient Jews and Christians would have divided the cosmos like this:

When Scripture speaks of God as “holy” (meaning “set apart” or “other than”), this is a glimpse into the depths of what it means. God is distinct and set from his creation. He cannot be fathomably lumped into the same category to which angels (and even satan!) belong. That’s a terrible way of looking at the world. God stands apart from everything—the eternal one, the Alpha and Omega. He, like the cheese, stands alone.

Everything else, both what we can see and what we cannot see, both what is sacred and what is desecrated, is grouped in the category of “creation.” In her new book Being God’s Image, OT Biola professor Carmen Imes illustrates how ancient Jews thought of the created order (Imes 2023, 20):

The scandalous nature of the incarnation is that God took upon himself the human project in Jesus the Messiah. In Jesus we see the very embodiment of spiritual and physical. In the hope of the world to come, we hold onto the certain expectation that the dwelling place of God will be conjoined with humanity (Rev. 21:3)—that God will take up residence within his creation. Fundamental to the truth upon which Christianity has staked itself is that what is “spiritual” is both seen and unseen. The Spirit of God superintending the growth of my tomato plants in my garden this summer is a spiritual event, inasmuch as God healing someone around which a group of his people are gathered to pray. It may seem less miraculous and more ordinary, but it is just as spiritual.

What, then, of the Spiritual vs Physical Resurrected Body?

Some point to Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 15:35-49 as a point of order. They point out that Paul is drawing a distinction between “spiritual” and “physical” in a way that makes sense to our modern distinctions. Paul specifically cites that we will receive a “spiritual body” as glow-up from our “physical body” (as translations like the RSV render it).

Except that he doesn’t. That’s what has been translated in English, but the Bible wasn’t written in English. Paul’s words were first written in Greek, and that’s not what is being said here. In his modern classic on the final resurrection, Surprised by Hope, N.T. Wright puts it like this (and also clarifies it in his own New Testament for Everyone translation):

The first word, psychikos, does not in any case mean anything like “physical” in our sense. For Greek speakers of Paul’s day, the psychē, from which the word derives, means the soul, not the body.

But the deeper, underlying point is that adjectives of this type, Greek adjectives ending in -ikos, describe not the material out of which things are made but the power or energy that animates them. It is the difference between asking, on the one hand, “Is this a wooden ship or an iron ship?” (the material from which it is made) and asking, on the other, “Is this a steamship or a sailing ship?” (the energy that powers it. Paul is talking about the present body, which is animated by the normal human psychē (the life force we all possess here and now, which gets us through the present life but is ultimately powerless against illness, injury, decay, and death), and the future body, which is animated by God’s pneuma, God’s breath of new life, the energizing power of God’s new creation (Wright 2008, 155-56).

So again, Paul is not pitting the spiritual against the physical. The future hope, as the ancient creeds put it, of the resurrection of the body and the life of the world to come, is one that is very much physical, but also very much animated with the intimate abiding presence of God’s spirit.

Concluding Thoughts: Why is this important?

When we have a low view of the physical, not only do we pattern our cosmology after something not found in Scripture, but we diminish the holiness of creation—including our own bodies—here and now. How we steward the present age speaks as a witness to our hopeful expectations of the next age. If we think we’ll inherit some sort of ghost-like immaterial existence in the age to come, the way we steward our bodies will be impacted. If we believe that the created order will be scrapped into a giant cosmic garbage bin at the end of the age and we’ll all just float away on clouds playing harps—that impacts our stewardship of creation.

But God called the physical good, in Genesis. He called you and I very good. The very nature of the Scriptural story is the beautiful tale of the Creator—who is set apart, distinct, and holy—and yet has come near, abiding with his people, working among his creation (in both ways that are ordinary and ways that are miraculous), and will one day unite and renew his creation under the lordship of Jesus the Messiah.