12 Things I With Everyone Knew About the Bible (Part 2)

Last week I shared the first five of twelve things I wish everyone knew about the Bible. This week I share the remainder of my list. (Ps…these are some of the spicier takes on the list, so heads up!)

6. The Bible is one story.

Yes, the Bible was written over a period of 1,400 years by at least 40 attributed authors in three languages (Greek, Hebrew, and a wee bit o’ Aramaic). Yes it is a collection of between 66 books (among Protestants) and as much as 81 books (in the Orthodox Tewahedo canon of the Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Churches). But despite this tremendous diversity, it tells one singular story or, a metanarrative.

That singular story is the story of God’s mission to reconcile and redeem his creation and to live in covenant with his people. This story reaches its pinnacle in the God-man Jesus, the perfect image of the invisible God (Col. 1:15). Once we begin to see the Bible as one, cohesive whole, it forces us to stop approaching the Bible like an answer book (I personally despise the corny acronym for the Bible “Basic Instructions Before Leaving Earth”). The Bible is not a Magic 8 Ball that we come to for random, disconnected answers any time we have a problem. It is a treasured ancestral story which we steward and in which we participate—the ever-unfolding story of God’s redemption of creation, coming to its fullness in the return of Jesus and the renewal of all things.

7. The beginning of the story is not about the material origins of the universe.

This one is a hard pill for many to swallow because we Americans have lived through a century of creation theology that is a reaction against evolutionary science. Creation theology has become largely hijacked by the culture wars, so we demand answers from Genesis 1-3 as though it were a science textbook. This is why I appreciate the work of people like John Walton, whose work (especially his Lost World Series) helps us understand the creation story in its original context.

Walton notes that when the ancients spoke about something coming into “existence,” they were not referring to its material origins (how it physically got here) but to its functional origins (when it was set apart for its purpose). When teaching on this subject, I often use the example of planting a church. When Tara and I church planted, there was the moment when the incorporation and non-profit status was approved—the church “materially” came into existence. But when people ask me when we planted our church, I don’t point to the time of its incorporation, I point to when we held our first service in 2015–when it was functionally set apart for its purpose.

This is the story of Genesis 1-2–a scene that opens when the universe has already been materially created (yes, by God) and is telling the story of humanity’s purpose (summarized in no small part in Genesis 1:27-28) to steward creation on behalf of YHWH, expanding the sacred space of the garden under his wisdom—and to reflect the praises of creation unto him. When we make the creation story about calculating the age of the earth and determining at what point dinosaurs showed up, we miss out on the beauty of the message. And that message is far more important than whatever scientific insight we might squeeze from its pages.

8. Sin is individual, communal, and systemic.

Sin is not so much the breach of arbitrary rules and regulations that God puts on people because he likes to harsh peoples’ mellow. In popular culture we often see the church painted as God’s “fun police,” here to put a stop to any hint of people having a good time. But sin is fundamentally related to departures from God’s very good design for his creation. That tendency to being, as the old song says, “prone to wander” does have deep, individual implications that we see throughout the pages of Scripture—Scriptures that were written to people in collectivist cultures and often needed to be reminded of individual responsibility regarding sin.

But we live in a highly individualistic culture, prone to overlooking how deeply interconnected we all are. We do not live our lives in isolated laboratory chambers, unaffected by those around us. We are impacted by the decisions of others—not only in how someone else’s sinfulness hurts me, but also in how someone’s sin has a conditioning effect on those they influence.

So let’s consider racism or ethnic prejudice. Certainly individuals bear the responsibility for their racist thoughts, words, and actions. But when people’s racialized sin exists in proximity to that of others who harbor the same sinful tendencies, this grows into a communal issue—and the community’s failure to deal with that sin is, itself, a communal form of sin. But as humans live in community with one another we establish cultural systems—government, economics, art, technology, etc—these are systems that act as binding elements, holding our communities together. Like a cancer, sin can spread into these systems by way of the communities that create them.

Scripture most frequently speaks of communal and systemic forms of sin in the story of Israel and Judah’s waywardness and/or communal responsibility. Ezekiel in particular addresses systemic sin at length in his rebukes of the government of Jerusalem failing to care for the vulnerable in the city.

9. What looks like errors and contradictions in the Bible are often misunderstandings between cultures.

Often when we see apparent errors or contradictions in the scriptures, it’s easy to get a bit bugged out or to jump to “fundamentalist” answers—either Scripture is wrong and therefore not God’s word, or Scripture must be right so there must be a logical, face value explanation available on the internet.

But neither of these are helpful. I have found that most misunderstandings about Scripture’s accuracy actually stem from failing to understand the cultures who first wrote and received the Scriptures—the cultures about whom the stories are written!

Take, for example, discrepancies about the order of events in the gospels, the feeding of the 5,000…or 4,000?, and more, strike us modern readers as odd. That is because, conditioned by centuries of high regard for the Western legal system, we associate the truthfulness of something with the accuracy of something. Like a witness, recounting the events with scientific and chronological precision, we seek to accurately describe something as exactly it had happened.

The ancients, however, including the gospel writers, were more concerned with theological precision. The gospel writers, including Luke’s Acts sequel, were more concerned with their high-context culture readers understanding the underlying theological point being made rather than crafting a chronologically accurate account of events. So did Jesus wander in the desert for 40, literal 24 hour days? Possibly, but not necessarily—and it’s really not important. 40 is a number associated with completion of purpose and is used a round number for a period of time under God’s providential supervision. So the fact that Jesus has spent this season of trial in the abiding presence of his Father is the underlying theological point and is more important than whether he was there for 40 literal days or something close to that.

10. The cultures of the Bible were not individualistic.

I describe this in a bit more detail here. While we in the West tend to view ourselves as the center of the universe, those in collectivist cultures today, as well as those of the Bible, thought very differently. For collectivist cultures, they tend to view themselves in light of the greater whole. They’re not the “rockstar” but one of many stones building something great.

This makes concepts like community harmony (i.e., shalom) and unity critically important priorities for the first Christians. Sin, in large part, was understood to be a breach of shalom (sometimes referred to as losing face, shaming, etc.). For Paul, his two chief priorities in his letters appear to be the harmony of the Christian community and, related, the witness of the Christian community to the broader community.

We have much to learn from this sort of cultural perspective, beckoning us away from some of the excesses of our individualism. We can learn much by listening to and considering the perspectives of majority world Christians today, many of whom (though not all) live in similar collective cultures like those of the first Christians.

11. Your body is more than “just a shell.”

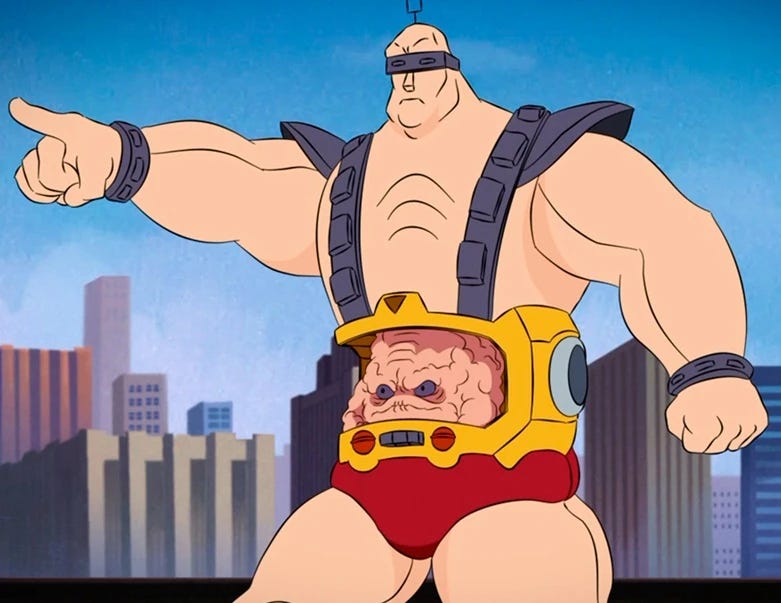

You’ve probably heard this a time or two—especially when a well meaning preacher is attempting to emphasize the hope of eternal life we have because of the resurrection of Jesus. The problem is that the idea that you and I are simply spirits inhabiting a body—as though we are all Krang from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles—is more closely aligned with Plato than it is Jesus.

Platonists taught that the soul (or spirit) was imprisoned in the body and would be freed from the body upon death. In platonic thought the material world was inherently corrupt while the immaterial (what we would call “spiritual”) world is superior. But this is not what Scripture teaches us.

Paul repeatedly emphasizes, especially in 1 Corinthians 15, that the hope that we have in the resurrection of Jesus is a bodily resurrection. Just as God raised Jesus in his resurrected body (note: not a new body, but rather his crucified body renewed and made incorruptible), so too we will enjoy a bodily resurrection at the end of the age. For Christians, the hope that we have is rooted in the unchanging truth that God’s very good creation is, well, very good. And he hasn’t abandoned that project—your body included.

So how we steward our bodies matter, because they are part of what make us fearfully and wonderfully made by our Creator. This is why Christians have historically buried, instead of burned, those who have fallen asleep in Christ. It is a statement about what we believe is to come.

12. The end of the story is not about the Sweet By and By.

Similar to the previous point, the end of the age is not about going somewhere else. Yes, Scripture promises that when we fall asleep in Christ (notice, I rarely use the word “die” when referring to Christians?) our spirit is at rest in heaven. But, as N.T. Wright says, “heaven’s great but it’s not the end of the world.” Meaning, that there is something that comes after heaven that is described to us by Paul in 1 Thessalonians 4 and by John in Revelation 20-22. The promise of eternity is that the dwelling place of God is with people (Rev. 21:3). The second coming of Christ is not a cosmic Uber ride to the Sweet By and By. No, John’s vision describes a great renewal and conjoining of heaven and earth. The two become one, as it were. And ruling over it all is the risen Jesus. This means that how we steward the earth speaks to what we believe about the life of the world to come. It means that we hold fast to the reality that God loves his creation and we will continue in partnership with him stewarding it under the wisdom of Jesus and under the power of the Spirit, just as we were entrusted to do in Genesis.

When I teach eschatology to Bible College students, I set out at the beginning letting them know that I really have no interest in teaching them a particular millennial theory or timeline. It ultimately makes little difference. What I’m interested in is that they walk away from the class emphasizing the same eschatological hope that has been taught to us from the testimony of the apostles and the apostolic fathers (that is, the generation who came after the apostles). This hope—our end times focus—is put simply in the words of the Nicene Creed: we look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. It’s really that simple. It’s really that beautiful.